Sean Scully was born in Dublin on 30 June 1945 into a family of very humble origins. “I was born in Dublin, where we lived like gypsies with nowhere to go. We moved home every six months”, the artist himself says. “We moved to the worst suburbs in London. By the time I was five we had already lived in more than ten different homes, so I had a clear feeling of instability.”1 At the age of seventeen he began working at the Victoria Palace Hotel in London, from where he escaped almost every day to look at Vincent van Gogh’s painting entitled Van Gogh’s Chair (1888) in the National Gallery in London: an old chair with a straw seat in which those lines that were to become so characteristic of Scully’s work can already be seen.

In 1973 Scully had his first solo exhibition at the Rowan Gallery in London. The show was a great success and he sold all his works. He decided to move to what was then the capital of art, New York, where he joined the predominant movement in the city at the time: Minimalism. As the art critic Arthur C. Danto points out: “It was consistent with this spirit that he should leave Britain for America to settle in New York, which he viewed as the promised land: he felt that the tradition of great painting was alive in the work of Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, much in the way classical learning had been kept alive in European monasteries – points of civilization and illumination within the surrounding cultural darkness.”2

In 1977 he held his first solo exhibition in New York at the Duffy-Gibbs Gallery and a year later he began giving classes at Princeton University. When Scully arrived in New York his work became very Minimalist. As he himself explains: “The color was reduced right down. What I did when I went there was really to strip myself right down to nothing, basically – as far down as I could go without having a thing.”3

However, Scully was immersed in the search for a style of his own, so he decided to break with Minimalism. “For five years I was making extremely Minimalist paintings. I was a well-respected member of the New York artistic community, but in 1980 I broke with Minimalism. This brought indignation from my artist friends. People looked at my new works and said ‘what the hell is this?’ Suddenly I introduced emotion, colour, relationship and descriptive titles like Empty Heart, The Bather, Adoration… they were titles that were not allowed in the puritanism of Minimalism.”4

He had now found his own idiom, which led to him exhibiting in the most prestigious museums and art centres, such as the Metropolitan in New York, the National Gallery in London and the Albertina in Vienna. In 2012 Scully was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in London and he has been a Turner Prize finalist on two occasions (1989 and 1993).

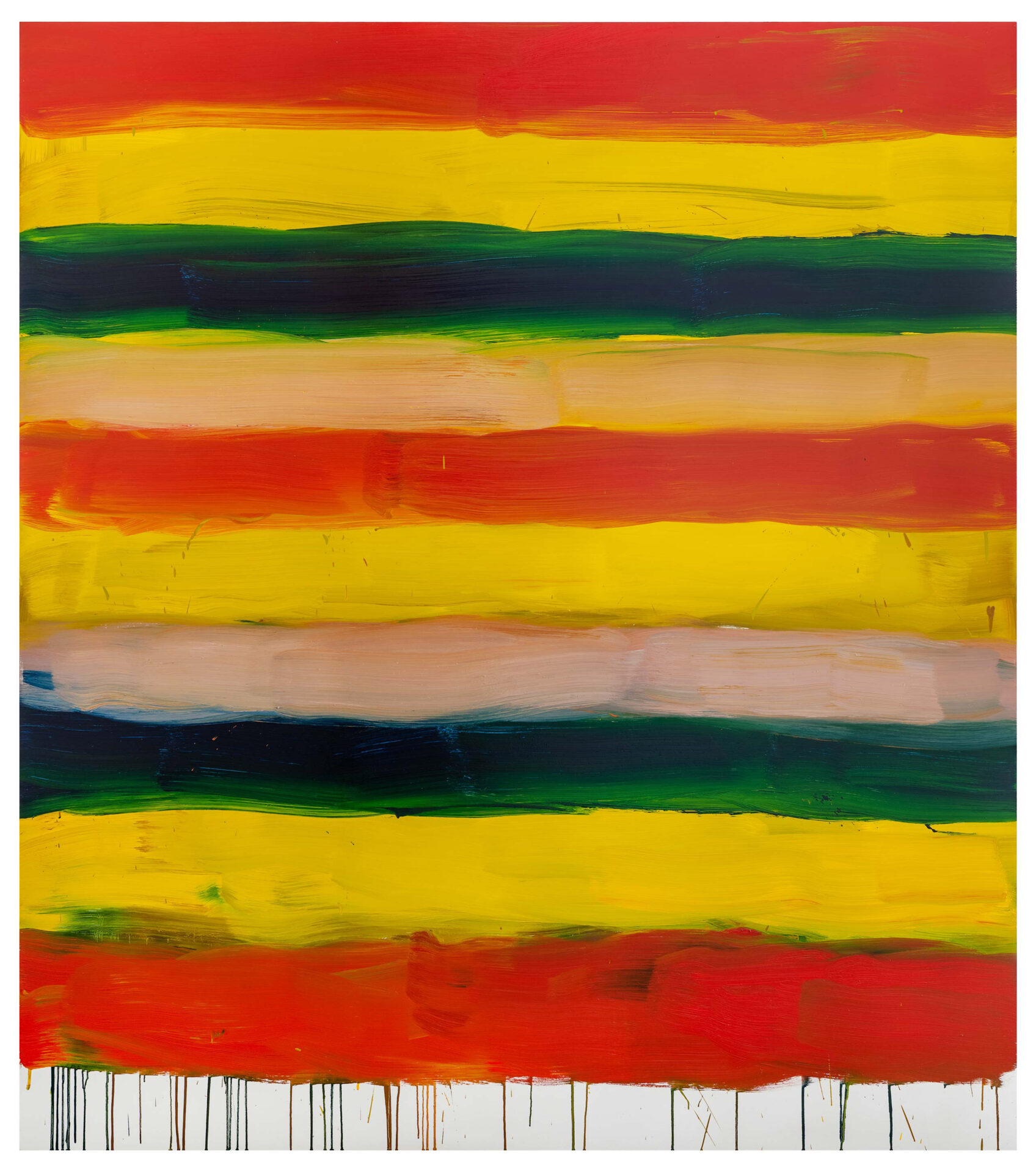

After visiting Scully’s show at the Venice Biennale in 2019 and seeing the stained-glass windows he made at the Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore, Hortensia Herrero suggested to Sean Scully that he should carry out an intervention in the former chapel of the Palacio de Valeriola. It consisted of the stained-glass windows for this space – two rectangular, one square and the windows in the dome – and the painting Landline Heat (2020). In the series of works called Landline, Scully embodies another constant element of his work: the lines of the horizon. As the artist himself points out in a text he wrote in July 2001 in his studio in the German town of Mooseurach: “I try to paint this, this sense of the elemental coming-together of land and sea, sky and land, of blocks coming together side by side, stacked in horizon lines endlessly beginning and ending – the way the blocks of the world hug each other and brush up against each other, their weight, their air, their color, and the soft uncertain space between them.”5 A distinctive feature of the Landline in the Hortensia Herrero collection is that it contains drips of red paint at the bottom which remind us of the blood of Christ, an element very much present in the Christian imagery of Catholic churches and chapels.